For centuries there was little love lost between the Highlanders of Scotland and their cousins in the Lowlands. The Lowlanders regarded the Highlanders as barbarian brigands who spoke an incomprehensible variation of the “Irish tongue”.

The Scottish Government was not slow to take advantage of this antipathy when it wanted to coerce the Presbyterians of Lanarkshire, Renfrewshire and Ayrshire in 1678 into accepting the Bishops of the Episcopalian church. It was decided to quarter 3,000 Highlanders on the Presbyterian counties in a man-made plague of plunderers. The 2,000 regular army troops who accompanied the so-called Highland Host on its terror mission actually behaved worse than the Gaels, but Lowland bile was focused on the latter.

So, perhaps it should be no surprise that the sons and grandsons of the Lowlanders who had been forced to endure the Highland Host, relished the chance to revenge themselves in the heart of Lancashire 47 years later.

Although the fighting in Preston in 1715 involved a number of English dragoons, the fiercest fighting involved Scot-on-Scot action.

The Highlanders were in England in the hope of sparking a rising of English Jacobites against their new German king, George I, who had been imported a year earlier to ensure a Protestant sat on the throne following the death of Queen Anne.

The best of the Government troops sent to intercept them were the men of a Scottish regiment originally raised in Lanarkshire from strict Presbyterians. The Cameronians in their first battle in 1689 had played a major part in stifling an attempt that year to restore the Catholic James II and VII to the throne.

In 1715 regiments were still known by the name of their colonel and rather confusingly considering the scene of the battle, the Cameronians were known as Preston’s Regiment, their colonel being George Preston.

The Cameronians had been part of the legendary Duke of Malborough’s army in a bloody war the bloody fighting against France and her allies on the continent. With the return of peace, the regiment had been sent to Ireland in 1713. But when the Earl of Mar raised the standard of rebellion at Braemar in 1715 the Lowlanders were rushed to England.

Bobbing John

Mar, known as Bobbing John for his dubious loyalties and dithering, threw away what was to prove the best chance of a successful Stuart restoration by failing to advance much further south than Stirling. The wheels would eventually come off the rebellion at Sheriffmuir on 13th November 1715 following an inconclusive and confused clash with Government troops commanded by the Duke of Argyll.

But before Sheriffmuir, Mar managed to slip a force of around 1,600 Highlanders across the Firth of Forth from Fife to East Lothian. The Jacobite force was commanded by Brigadier William Mackintosh of Borlum, a beetle-browed veteran soldier who had spent much of his military career in the French Army. The core of the Highland force was the 700-strong Mackintosh Regiment under the command of Lachlan Mackintosh of Mackintosh, the clan chief and a nephew of Borlum’s. The rebels under Borlum also included a number of men from the Eastern Lowlands, many of them from Aberdeenshire, Perthshire and Angus.

Mackintosh and his men made their way via Leith to Kelso where they joined forces with a small army of borderers and Galloway men under Viscount Kenmure. A number of English Jacobites from Northumberland, led by the local MP Thomas Forster, also joined Mackintosh and Kenmure. The Earl of Mar decided for political reasons that Forster should command the Jacobite army in England.

Mackintosh and his Highlanders were appalled by both the quality and quantity of the English rebels. It was only with the greatest reluctance that Mackintosh was persuaded to advance into England. Government troops under Lieutenant General George Carpenter blocked the route south through Northumberland and Durham and it was decided to raise a Jacobite army in Lancashire, which was believed to be sympathetic to the Stuart cause. A number of the Scots, perhaps as many as 500, slipped away during this period.

The defections were not made up by a successful recruiting drive on the march through Westmoreland and Lancashire. Very few men joined the Jacobites as they progressed through Appleby, Kendal, Kirby Lonsdale and Lancaster. At Lancaster, the rebels seized six ships’ cannon.

By the time the Jacobites reached Preston on 9th November they numbered somewhere between 3,000 and 4,000 men. Preston was one of the biggest towns in Lancashire at the time and stood at the junction of the Lancaster, Wigan, Clitheroe and Liverpool. The stop at Preston was supposed to be brief and was expected the rebels would soon advance on Liverpool. But “General” Forster proved a ditherer.

While Forster dithered Lt-Gen. Carpenter was closing in on him from the north east with 2,500 men, mainly poorly trained dragoons. And Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Wills was moving north from Wigan with 2,200 men, again mainly poorly trained dragoons but also including the veteran infantry of the Cameronians.

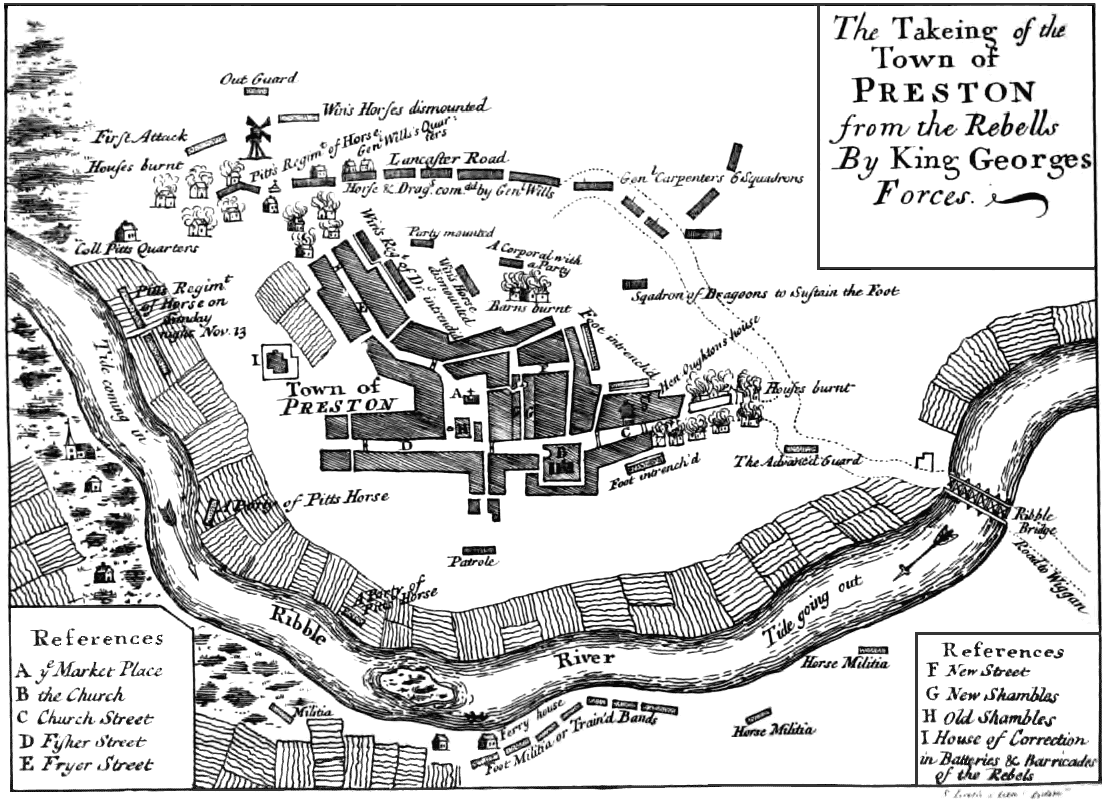

When he learned of Wills’s approach, Forster ordered his men to prepare to defend Preston. Or, more probably, Forster allowed Mackintosh of Borlum to put the town in a state of defence. This consisted of putting barricades across the main roads into the town and the major thoroughfares. Several large houses at key points were turned into fortresses and chains were placed across several possible access points.

Preston 1715

Preston 1715

As Wills was coming from the south, it was expected the main Government attack on 12th November would come along the Wigan Road which led into the market place of the town from the south east. It was here, on Church Street, that Mackintosh took command of the barricades. A force of 100 men under the command of Farquharson of Invercauld, the Mackintosh battalion’s second-in-command, was sent to the narrow bridge across the River Ribble but pulled back into Preston as the Cameronians approached. There were several fords on the river and Invercauld would soon have found himself surrounded and cut off.

Wills was surprised to find the bridge undefended and no rebels holding the narrow hedged road into Preston and moved forward cautiously. But he had little time for the rebels and believed the defence of the town would collapse when Government troops pushed through the barricades.

He split the bulk of his force into two columns. One, under Brigadier Philip Honeywood, and spearheaded by the Cameronians would enter the town via Church Street. The second column, commanded by Brigadier James Dormer would swing north and attack down the Lancaster Road. This road was defended by two barricades in succession which were manned by the Mackintosh Regiment under Lachlan Mackintosh. The first barricade was known as the Windmill Barricade.

Cameronians Attack

The Cameronians were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Baillie, better known as Lord Forrester of Costorphine. The commenced their attack around 2pm. They came under withering musket fire from the Highlanders manning the advanced barricade on the eastern edge of Preston and two large houses either side of it on Church Street.

The Cameronians, and to a lesser extent the English dragoons who accompanied them, suffered heavily. The Cameronians may have lost as many as 50 men killed or badly wounded. Accounts differ as to how successful the initial assault was. Wills would claim in his victory dispatch that the advanced barricade was stormed. Other sources suggest that although some of the Cameronians reached the barricade, they were driven back.

But it would appear that the Cameronians did succeed in gaining a foothold in Preston to the south of Church Street. A strong force braved the fire from the main barricade on Church Street to rush to the north side. They then fanned out into the side streets and alleys on the north side looking for a way around the Jacobites holding the main thoroughfare.

Mackintosh now withdrew the men holding the two large houses which dominated the east end of Church Street. The Houghton House had a large flat roof and may even have been built as a personal stronghold.

The main Jacobites behind the main barricade further west down Church Street held the Cameronians at bay, possibly aided by two ships cannons mounted on it. Though some sources suggest that the drunken sailor in charge of the cannon only managed to knock down a chimney.

Baillie made a personal reconnaissance of the alleys north of the advanced barricade despite sniper fire from the Jacobites. He decided to attempt to storm the barricade across Tithebarn Street from the Houghton House. This would have brought his men in behind the main barricade on Church Street and in a position to attack the Jacobite reserves at Preston’s Parish Church. The Tithebarn barricade was held by a rebel force under the command of Lord Charles Murray. The attack from the Houghton House came close to succeeding but was foiled by the timely arrival of 50 English gentleman volunteers from the Parish Church.

Baillie was shot in the face during the assault and after this the fighting at the east end of Preston slid into desultory sniping for the rest of the day. Mackintosh refused a point blank order from Forster to launch an attack aimed at driving the Cameronians and dragoons out of the town. It is likely the Scot feared that the pursuit would take his men beyond the limits of the town where they would be easy prey for the mounted dragoons waiting for them.

Around 4pm the second of the Government columns, under Brigadier Dormer, made a determined attack on the Mackintosh Regiment at the Windmill Barricade but it was driven back. A second assault down an alley called Black Ween which would have outflanked the barricade was also repulsed.

The Jacobite barricade on the Liverpool Road at the west end of Preston was not attacked and in fact Wills had no troops in the area. It is likely that this failure to block a principle escape route allowed a number of the English Jacobites to slip away on the night of the 12th.

A number of the Cameronians had been captured during the confused and desperate fighting at the east end of Preston. A total of 50 captured Government troops were held at the White Bull Inn where a Jacobite pastor offered to pray with them. The stubborn Scots told him “If you be a Protestant, we desire your prayers, but name not the Pretender as King.”

The Government troops at both the eastern and northern sides of Preston attempted to force the Jacobites out of their defensive warrens by setting fire to several houses. But as darkness fell, the fighting was stalemated.

Put a Candle in the Window

In a misguided attempt to identify who was occupying which houses, Wills ordered his men to display lighted candles. This attracted rebel snipers and the order was quickly countermanded. However, due to a misunderstanding, some Government troops lit more candles.

An early morning attack on Mackintosh’s barricade on Church Street was driven off and this marked the last of the real fighting. Around 9 am Lt-General Carpenter and his three regiments of dragoons arrived and completed the encirclement of Preston.

Mackintosh and his Scots wanted to break out through the Government cordon but Forster decided to surrender. The English MP’s lack of resolution almost cost him his life. A Highlander called Murray tried to shoot him at his headquarters but the barrel of his pistol was knocked aside at the last minute and he missed. Elsewhere in Preston Highlanders clashed with the remaining English Jacobites and blood may even have been spilled.

After much negotiation, mainly because the Highlanders refused to surrender, the Jacobites eventually capitulated on the 14th. Under the watchful eyes of the surviving Cameronians, the Highlanders paraded and piled up their weapons in Preston’s market place. The Scots were to guard their Highland prisoners and the English Jacobites captured with them in the Parish Church for almost a month. The Jacobite officers downed their weapons in the church yard while the noblemen were granted the privacy of the Mitre Inn for their surrenders.

Six captured Jacobite officers were immediately court-martialed following the surrender as deserters and four were executed by firing squad. One officer was able to prove that he had resigned his King’s commission before joining the Jacobites and Lord Charles Murray managed to engineer a temporary reprieve which was soon made permanent.

Most of the other senior Jacobite officers were taken to London. Six of them, including Brigadier Mackintosh, managed to break out from Newgate Prison. Forster was held at the same jail and apparently managed to walk out unchallenged after dining with the prison governor.

Only two of the nobles captured at Preston were executed for High Treason, the Scots Viscount Kenmure and England's Earl of Derwentwater. Fellow Scottish aristocrat Lord Nithsdale managed to escape from prison dressed as a woman. A casual observer might wonder how serious the Government was when it came to dealing with high-born Jacobites.

Around half of the 1,300 rank and file Jacobites captured were sold into seven year slavery in the American colonies and West Indies. One group of 30 prisoners managed to overcome the crew of the ship transporting them across the Atlantic and sailed it to France.

One in 20 of the prisoners were selected at random for trial in northwest England. Thirty-four of them were hung drawn and quartered in various towns at a cost to the English Treasury of £132 15s 4d. At least 43 prisoners died in jail.

Wills is believed to have low-balled his casualty figures in his victory dispatch when he reported 142 dead and wounded. This was probably due to criticisms of his decision to launch direct and costly assaults on Preston rather than surrounding the town and waiting for Carpenter. A number of mass graves were uncovered during 19th Century construction work in Preston and recent estimates put the total Government casualties at closer to 300 men. The Cameronians suffered 92 dead and seriously wounded. The Jacobites only lost 17 killed and 25 badly wounded.

Other articles you might be interested in -

*Here's one that combines Canadian and Scottish themes * Read about the blunder that made Canada an easy target for invasion from the United States - Undefended Border

*Read about the Second World War's Lord McHaw Haw

*Serious questionmarks over the official version of one the British Army's most dearly held legends - The Real Mackay?

* Read about the veterans of Wellington's Army lured into misery in the Canadian Wilderness in a new article called Pension Misery

*A sergeant steals the battalion payroll. It’s called Temptation

*Read about how the most Highland of the Highland regiments during the Second World War fared in the Canadian Rockies - Drug Store Commandos.

*January 2016 marked the centenary of Winston Churchill taking command of 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front. How did the man who sacked so many British generals during the Second World War make out in his own most senior battlefield command? Find out by having a look at Churchill in the Trenches .

*Just weeks before the outbreak of the First World War one of Britain's most bitter enemies walked free from a Canadian jail - Dynamite Dillon

*Click to read - - Victoria's Royal Canadians - about one of the more unusual of the British regiments.

*This is one of the most popular articles on the site - Scotland’s Forgotten Regiments. Guess what it's about.

*The 70th anniversary of one of the British Army’s most notorious massacres of civilians is coming up. See Batang Kali Revisited