Scottish Military Disasters

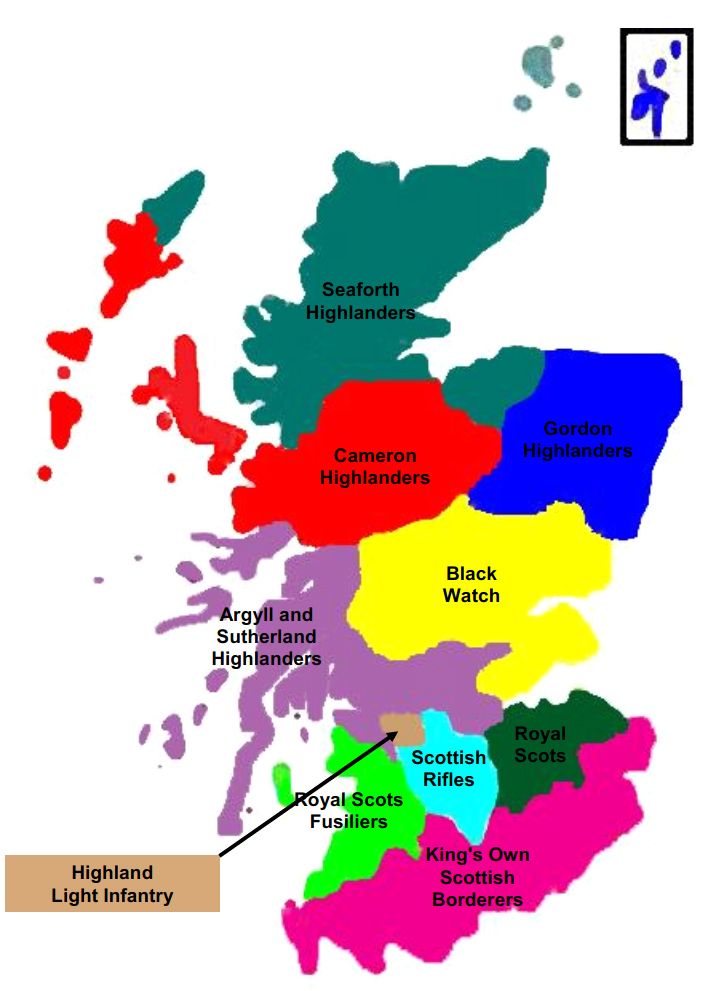

The counties assigned to the various Scottish regiments as recruiting areas by the time of the First World War were as follows –

Royal Scots – City of Edinburgh, County of Edinburgh (Mid Lothian), Haddingtonshire (East Lothian) and Linlithgowshire (West Lothian)and Peeblesshire.

Royal Scots Fusiliers – Ayrshire

King’s Own Scottish Borderers – Berwickshire, Drumfrieshire, Roxburghshire, Kirkcubrightshire, and Selkirkshire.

Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) – Lanarkshire and Parts of Glasgow

Black Watch – Fife, Forfarshire and Perthshire.

Highland Light Infantry – Glasgow.

Seaforth Highlanders – Caithness, Cromarty, Elginshire, Nairnshire, Orkney, Ross-shire, Sutherland.

Gordon Highlanders – Aberdeenshire, Banffshire, Shetland and Kincardineshire.

Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders - Inverness-shire.

Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders – Argyllshire, Bute-shire, Clackmananshire, Dumbartonshire, Kinross-shire, Renfrewshire and Stirlingshire.

The Royal Scots Greys and the Scots Guards recruited from across Scotland.

The reality was that apart from the territorial battalions at the start of both World Wars and during National Service the number of men serving in a regiment who came from its official recruiting area probably almost never exceeded 40%.

According to David French's book "Military Identities" between 1883 and 1900 the average percentages of men born in the assigned regimental recruiting area were -

Cameronians/Scottish Rifles - 38.1%

Black Watch - 36.4%

Highland Light Infantry - 25.4%

Royal Scots - 23.8%

King's Own Scottish Borderers - 21.8%

Gordons - 21.1%

Seaforths - 19.7%

Argylls - 19.1%

Royal Scots Fusliers - 10.6%

Camerons - 9.6%

Map

This is an improved version of the map in the Quick Guide to the Scottish Regiments courtesy of the Scotland's War team.

Who out there knows which war the 78th Fraser Highlanders fought in? Or where Keith’s Highlanders fought their battles? Whatever happened to the 70th Glasgow Lowland Regiment?

I’m guessing that some of you do – but my point is that history is not only written by the winners, it’s written by the survivors. The exploits of the Black Watch, Royal Scots, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and the Cameronians are all reasonably well known. But what about the regiments that were raised and disbanded in the space of a couple of years? Or the Scottish regiments which morphed into Irish or English regiments? Some of these Scottish regiments had fighting records which equalled the Black Watch or the Camerons, but they have been consigned to the dustbin of history.

The British Government has always tried to keep the Army as small as possible – often in reality too small to do all the jobs required of it. The “can-do” attitude and making do with inferior equipment that has characterised the British Army has often meant men, and these days women, have died unnecessarily – a look at Iraq and Afghanistan shows nothing has changed.

That desire to keep the Army small – also a legacy of a fear of military coup which dates back to the days of Cromwell – meant that many regiments were formed in wartime and quickly disbanded when peace was restored. The British Army is usually regarded as being established in the reign of Charles II. One of the first Scottish regiments to be raised, Lockhart's, only existed from 1672 until 1674. Charles wanted it to fight against the Dutch and to be trained as marine battalion. The number of Gaelic-speaking Highlanders in its ranks made it difficult for the regiment to work with English speaking sailors. Most of the regiment was captured by the Dutch and while many of officers were taken to the Netherlands as prisoners, most of the rank-and-file were dumped back on the south coast of England. The regiment was re-raised but disbanded about three months later when war against the Dutch ended in February 1674.

King William III had 15 Scottish regiments fighting for him in Europe between 1694 and 1697. Earlier, in 1692, no fewer than 11 of the 25 British regiments King William sent to Europe were Scots.

Those who have read Scottish Military Disasters will know that I pretty much wrapped up the story of the 71st Highland Regiment’s part in the 1806 invasion of Argentina with their surrender.

I thought it might be worth having closer look at their almost year in captivity. The 71st had formed the bulk of the troops detached from garrison duty in South Africa for the invasion of the Spanish colonies in South America – Spain being at war with Britain at the time. The British managed to seize Buenos Aires and shipped around one million dollars in Spanish treasure back to London. But when a small Spanish army approached the city in August 1806, the population rose against the tiny British force and it was forced to surrender. The terms of the surrender included a provision that the British would be allowed to leave Buenos Aires on British ships. But the Spanish did not honour the deal – possibly because more British troops were on their way to Buenos Aires.

The officers and men of the 71st found themselves attacked by mobs in the city as they were marched to the city hall where they were to be imprisoned. It was only the intervention of local priests and some of the wealthier citizens that prevented many of the soldiers from being lynched by the mob. The mobs spent several days trying to capture British soldiers not being held at the city hall. At least one was forced to hide under a bed to escape the howling mob and most were afraid to venture out in public unless escorted by a priest. A Royal Marine was not so lucky and was lynched. The bodies of British soldiers killed were often mutilated and stripped. Some citizens of the city wore severed British ears in their hats.

It was decided to disperse rank and file of the 71st amongst several settlements deep in the interior of Argentina. It was feared if the regiment was kept together it would overwhelm the guards and attempt to join a British army operating on the other side of the River Plate. The soldiers had their packs, which had been put into storage two days before the surrender, returned to them. But the contents had been plundered. Some of the troops found themselves being marched almost 600 miles to the foothills of the Andes. Crossing the waterless pampas plains, the ragged soldiers were forced to use animal excrement for fuel.

The exotic strangers found themselves welcomed into the remote communities and many of the soldiers with civilian trades soon found themselves plying them. The wealthier families in the communities to which the 71st were sent played host to the soldiers and generally treated them well. Many of the soldiers learned Spanish during their captivity and their proficiency in the language was to come in handy later in the war when the 71st fought on the Spanish side to liberate Spain from its French occupiers.

The officers, and at least one of the senior sergeants, were kept closer to Buenos Aires and at first allowed some freedom of movement. They were billeted on richer families and received $1 a day in allowances from the Spanish Government. But life was not all peaches and cream for the officers. Two were ambushed while out for a horse ride. Captain Ogilvie of Royal Artillery was lassoed and pulled off his horse before being murdered and his companion, Lieutenant Colonel Denis Pack, the 71st’s commanding officer, would have suffered the same fate if two passers-by had not intervened. An Irish woman who was married to one of the officers’ soldier-servants was murdered after being sent on an errand carrying a Spanish doubloon coin. Her two killers wept when they learned they had killed a fellow Catholic. One of the officer's servants was lassoed and dragged from his horse while out riding near the village of Capel. His attacker, or attackers, dragged the man, sadly not named, for some distance with a horse before slitting his throat from ear to ear.

The murders were used as an excuse to mount a guard on the officers but everyone knew the Spanish soldiers were jailers and not protectors. Pack managed to slip away from his minders while being moved deeper into the interior of Argentina and managed to reach British troops on the other side of the River Plate. There were accusations that Pack had broken parole, that he had given his word not to escape in exchange of freedom of movement. Pack demanded to be brought before a court of inquiry at which he successfully argued that as he was under guard when he escaped, he could not have been on parole.

Sergeant William Gavin was held with the officers. When he was told he was being shipped into the interior he tried to buy some food for the journey. He had no money, so he attempted to sell his watch to a Spanish friend. But the friend misunderstood and tried to thrust 30 to 40 doubloons on him with a promise of more. Gavin gave the money back.

In July of the following year the British suffered another defeat at the hands of Spanish troops and agreed to another evacuation. The men of the 71st were included in the deal but it took two months to bring them to Monte Video. They arrived dressed in civilian clothing, including ponchos.

It wasn’t until 27th December that the 71st finally reached the Irish port of Cork. There they found a year’s pay and at least £18 each as a share of the treasure captured at Buenos Aires. Barrels of beer and whisky were ordered from Cork and for several days some rooms in the 71st’s barracks were ankle deep in booze.

Not all the men in the regiment came back from Argentina. At least 30 and perhaps as many as 96 opted to remain on the other side of the Atlantic. These were said to have been Dutchmen recruited before the 71st left South Africa or Irish Catholics who preferred the comforts of life in Argentina to what awaited them back on their native soil.

Canada’s first overseas military adventure was not, as many believe, the South African War which broke out in 1899. Rather, the year 1858 saw Canadian troops fitted out in relic uniforms from the Napoleonic Wars sent to “avenge” the massacre of British women and children by rebels in India. And though the men of the 100th Regiment (Prince of Wales’s Royal Canadians) did not, in the end, reach the battlefields of India, they did provide fodder for the myth-makers of later generations.

The raising of the 100th Regiment was an experiment that proved so controversial that no further attempt was made to raise a Canadian unit for Imperial service for over forty years. Throughout its three decades of existence, members of the 100th clung tenaciously and eccentrically to their Canadian roots -- even after they were officially designated as an Irish regiment.

The 100th regiment was formed as a result of a surge of repugnance throughout the British Empire in 1857 at the news of the Bibighar massacre of white women and children during the Siege of Cawnpore in the opening stages of the Indian Mutiny (also called “Kanpur” by some Indian historians who refer to these events as the First War of Independence). Canadians joined in the outrage at “the Massacre of the Ladies” and rallied to the flag. But Canada’s offer of help came with strings attached and did not quite deliver what the British had been led to expect.

Controversially, as far as the British Government was concerned, Canadian volunteers responding to the Bibighar massacre were not required to purchase their commissions. At a time when British officers bought and sold their ranks, often regarding the final sale as their pension fund, the Canadian officers in the 100th were awarded their commissions based not on the size of their pocket books, nor on merit alone, but on how many recruits they secured.

The British Treasury presumably chafed at missing out on the income from the sale of commissions in the new regiment. Still, even when India, the jewel in the crown of Empire, was threatened, the British accepted that Canadians would not pay for the honour of coming to the rescue: “I do not know whether you have been in America, but you must be quite aware that you would never have got Canadians to pay the full price of the commissions,” Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Yorke told a parliamentary committee in 1859. The feeling at Horse Guards, British Army headquarters, was that few Canadians would, for example, pay £1,800 (almost $8,750 in 1858 terms) to become a captain.

British doubts about Canadians’ commitment to the Empire had been triggered when Canadian authorities blocked an earlier attempt by militia officers in 1854 to raise a regiment to fight the Russians in the Crimea in spite of public interest. The government of the Province of Canada claimed that the potential menace of the United States made it unwise to send men willing and capable of bearing arms out of the country. But some cynics suggested that the real reason for refusing military aid was that, with a shortage of unskilled labourers, removing 1,000 men from the workforce to send a token force to the Crimea would drive up wages.

Three years later, the news of hundreds of women and children being murdered on the north-east plains of India by rebels prompted Canadian militia officers to revive the attempt to fight abroad in Queen Victoria’s name. The treacherous slaughter of 200 women and children in the Bibighar at Cawnpore in 1857 shocked newspaper readers across the English-speaking world.

The Province of Canada was already flexing its nationalist muscles. With Canada’s eager eyes cast to the West, Confederation was only ten years away, and many in the Province relished the chance to play a role in saving the Mother Country. But even then, elections took priority over rescuing the Empire. It was only after the votes had been tallied that the Governor General, Sir Edmund Head, began to raise the battalion that would continue to carry the maple leaf on its insignia until it was disbanded in 1922.

The rank-and-file element proved to be controversial. In 1899, when Canadians were raising units to fight in the Second Boer War, the soldiers of the old 100th were eulogized as the cream of Canadian manhood. That was certainly what the British believed they were getting in 1858. But most of the volunteer recruits turned out to be British-born and the 307 Irishmen among them formed the biggest single group. Only 268 of the first 866 were born in Canada. The British could be forgiven for feeling that it would have been cheaper to recruit a regiment in Ireland than pay to ship one across the Atlantic.

They were a mixed bunch. James Dickie had already deserted from the British Army twice. Shoemaker John Mackay deserted the 100th before he had even been issued a uniform. Other recruits made headlines when they went on a rampage in Quebec City and attacked civilians and homes at random. Order was restored by troops from the British 17th Foot, garrisoned at the Citadel at the time.

Recruiting stations were set up in Toronto, Niagara, Kingston, London, Montreal and Quebec City. The office set up in the Globe Hotel on Yonge Street in Toronto signed up 40 recruits in short order. There was a ban on recruiting men from the United States. Only British subjects were to be accepted. The £3 bounty paid to each recruit came from the British Treasury, which also met the cost of shipping the regiment across the Atlantic. Military storehouses across Canada were ransacked to provide uniforms and equipment. But all that could be found were musty leftovers from the War of 1812.

A young officer in the 100th regiment reported that when the regiment arrived in England many people believed they were seeing a ghost army of soldiers from the Duke of Wellington’s time.

“It only lacked ‘pigtails and powder’ to make it appear as if one of the Duke’s veteran battalions of the Peninsula had come to life,” Ensign Charles Boulton remembered. “Especially curious to the people of England was the motley  uniform of the 100th, for the old coatee had long been forgotten; and on our arrival in England we marched to Shorncliffe Camp in this picturesque obsolete uniform.” Boulton knew a thing or two about old uniforms. The 16-year-old had borrowed an ancient one belonging to a family friend before setting out, with a bagpiper in tow, to raise forty recruits in Peterborough, Lindsay, and Campbellford.

uniform of the 100th, for the old coatee had long been forgotten; and on our arrival in England we marched to Shorncliffe Camp in this picturesque obsolete uniform.” Boulton knew a thing or two about old uniforms. The 16-year-old had borrowed an ancient one belonging to a family friend before setting out, with a bagpiper in tow, to raise forty recruits in Peterborough, Lindsay, and Campbellford.

Not all the officers in the regiment were as lacking in life and military experience as Boulton. A guiding force behind the regiment was Canada’s first winner of the coveted Victoria Cross for extreme valour. The 100th's Major Alexander Dunn had won the VC in 1854 in the fabled Charge of the Light Brigade. In that famous noble folly he had twice gone to the rescue of dismounted British troopers who were about to be cut down by pursuing Russian cavalry. But his career with the 11th Hussars had come to a premature end when he eloped with a brother officer’s wife. To save face Dunn returned to civilian life in Canada -- but rejoined when the 100th was formed. (A product of Upper Canada College and Harrow school in England, Dunn stood at the opposite end of the social spectrum from the second Canadian to be awarded a Victoria Cross, Seaman William Hall, the Nova Scotia-born son of escaped American slaves.)*

The British had insisted on posting more than a dozen experienced officers, several of whom had already seen action against the Indian rebels, to the 100th in an effort to make it fit for combat. But by the time the regiment arrived in England in the summer of 1858, the worst of the fighting in India was over. New uniforms were issued, without buttons at first, and the regiment was drilled by sergeants from the elite Brigade of Guards. But instead of India, the Canadians were sent to garrison the British fortress at Gibraltar at the western mouth of the Mediterranean. This posting to a relatively tranquil outpost of Empire could not, in all truth, be regarded as a vote of confidence.

However, in 1862 the 100th did enjoy grandstand seats for an episode in the American Civil War when the Confederate commerce raider C.S.S. Sumter intercepted and burned two US merchant ships, the Neapolitan and the Investigator, within sight of Gibraltar. The Sumter then took refuge at the British outpost and Boulton would later claim that the regiment’s officers played host during these events to officers from both the Confederate vessel and the seven United States warships sent to prevent it from leaving Gibraltar.

The following year saw the 100th sent to Malta. Victoria Cross winner Major Dunn# had bought command of the regiment in 1861. It was on the island -- another quiet British outstation of Empire -- that 21 members of the regiment were lost to cholera. It was also where the regiment finally first drew blood – if the riot in Quebec is excluded from the record. A massive shark was spotted basking at one of the regiment’s favourite swimming places on the coast. Sergeant Charles Seymour, later a detective with the Toronto Police, armed himself with a large knife and dived into the water. The shark’s head was mounted and kept as a regimental souvenir.

Closer to home, the threat of invasion in British North America by members of the Fenian Brotherhood, many of them veterans of the American Civil War, bent on pressuring the British to set free their native Ireland -- brought the 100th back across the Atlantic in 1866. Many of the original Canadian members still serving took the opportunity to go home and to leave army life behind. Although the Canadian character of the regiment had begun to dilute almost from the moment it had set sail from Quebec City in 1858, it remained stubbornly proud of its roots. The regiment paraded in Ottawa on 1st July 1867 with its headgear adorned in maple leaves to celebrate Confederation. And for years afterwards a consignment of maple leaves was sent from Canada to wherever the regiment was serving for the men to wear on July 1.

The Canadian connection had been briefly strengthened during the regiment’s two-year stay in the country but after it sailed back to Britain in 1868 Canadian recruits again became rare. Despite this, the regiment’s cap badge, belt buckle, and colours (the regimental flag) continued to include maple leaf motifs. The regiment also decorated its drums with paintings of beavers and maple leaves.

There were also attempts to encourage nicknames for the regiment such as “the Beavers,” “the Maple Leaves,” or “the Colonials.” In 1875 the officers succeeded in having the War of 1812 battle honour “Niagara” added to the regimental colours. The honour had actually been earned by a previous, long-disbanded, regiment which bore the number 100th Foot, the Prince Regent’s County of Dublin Regiment, which the 100th could claim to have perpetuated. The colours, complete with their “unearned” battle honour, was donated to the Canadian government in 1887 when new colours were presented to the unit in India.

When the British Army was restructured in 1881, the 100th became the 1st Battalion of the Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians). Its training depot and headquarters were in Ireland. But the battalion continued to cling to its now very tenuous Canadian connections. When the 1st Leinsters arrived in Halifax in 1898, one of the officers asked a Nova Scotia journalist to call the unit the 100th Canadians. The journalist was told, as evidence of the unit’s association with his country, that the regimental band always played “The Maple Leaf” before “God Save the Queen” and the dinner plates used by the officers were not only made in Canada but were decorated with maple leaf and beaver motifs.

It was perhaps fitting that when the 1st Leinsters sailed from Halifax in 1900 they were the last British soldiers to serve as garrison troops in Canada. The battalion, which had now been in existence for forty-two years, was finally going to war. The 1st Leinsters served with distinction in the Boer War and the First World War, carrying their old title “the Royal Canadians” into the trenches in France.

A more final end came in 1922 when the Leinsters were amongst the regiments disbanded following the creation of the Irish Free State. In a last homage to its Canadian roots, the 1st Leinsters’ regimental silver was donated to the Royal Military College in Kingston. The assorted silverware included a miniature canoe and a model of a sled -- fitting tokens of their Canadian origins in a vain, if noble, attempt to come to the defence of the Raj.

*Hall was awarded the Victoria Cross in February 1859 for his bravery in keeping his cannon in action at the Relief of Lucknow in November 1857, while on attachment to the army from HMS Shannon. Canada’s Surgeon Herbert Reade was not awarded his VC until February 1861, though it was for acts of bravery performed two months before Hall’s actions at Lucknow.

# Dunn was to die in a mysterious shooting incident in Ethiopia in 1868 after becoming commanding officer of the 33rd Duke of Wellington’s Regiment in 1864. The official version at the time was that he shot himself accidentally while hunting. But some suggested it was a suicide. Others went even further, suggesting a cuckolded husband might be responsible, or pointing out that Dunn's only companion on the hunting trip, his manservant, was also the main beneficiary in his will.

This article first appeared in the Autumn/Winter 2013 edition of the Dorchester Review

Other articles you might be interested in -

*Here's one that combines Canadian and Scottish themes * Those who enjoyed reading about the Royal Scots’ Armistice Day battle with the Bolsheviks in 1918 might be interested in the same fight as seen from a Canadian viewpoint - Canada’s Winter War

* Read about the blunder that made Canada an easy target for invasion from the United States - Undefended Border

* Read about the Second World War's Lord McHaw Haw

* Serious questionmarks over the official version of one the British Army's most dearly held legends - The Real Mackay?

* Read about the veterans of Wellington's Army lured into misery in the Canadian Wilderness in a new article called Pension Misery

* A sergeant steals the battalion payroll. It’s called Temptation

* Read about how the most Highland of the Highland regiments during the Second World War fared in the Canadian Rockies - Drug Store Commandos.

* January 2016 marked the centenary of Winston Churchill taking command of 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front. How did the man who sacked so many British generals during the Second World War make out in his own most senior battlefield command? Find out by having a look at Churchill in the Trenches .

* Click to read - - Victoria's Royal Canadians - about one of the more unusual of the British regiments.

* Read an article about the Royal Scots and their desperate fight against the Bolsheviks on Armistice Day 1918 - Forgotten War A second article, looks at the same battle but through a Canadian lens .

* This is one of the most popular articles on the site - Scotland’s Forgotten Regiments. Guess what it's about.

*********The 70th anniversary of one of the British Army’s most notorious massacres of civilians is coming up. See Batang Kali Revisited

2023

The 2023 Book of the Year had only two strong contenders. Though I think the number of good books in the past 52 weeks was higher than in a couple of recent years. It came down to Secrets of the Conqueror or Fly for Your Life. By a whisker, journalist Stuart Prebble's book about the submarine HMS Conqueror just pipped Larry Forrester's biography of Spitfire ace Robert Standford Tuck. Forrester's stupid assertion that the USA declared war on Germany in 1941 may or may not have tipped the balance. For it was a lively, colourful and at times touchingly frank biography. Prebble is good on the Conqueror's controversial sinking of the Argentinian cruiser Belgrano during the 1982 Falkland's War, better on the disgraceful cover-up that followed and excellent on the top secret mission that was undertaken by the sub following the war.

Honourable Mentions for CV Wedgewood's The Thirty Years War, Richard Collier and Philip Kaplan's Battle of Britain 50th Anniversay book Their Finest Hour, Antony Beevor's The Second World War, Philip Zeigler's Omdurman and Martin Windrow's realistic look at the French Foreign Legion and France's colonial wars between 1870 and 1935, Our Friends Beneath the Sands.

2022

Book of the Year Well, the 2022 Book of the Year sees a milestone result. We have our first by a previous winner. And it is co-incidence that that winner is a Scot. Anyway, enough faffing about - the 2022 Book of the Year is The Yompers by Ian Gardiner. Gardiner was a company commander in 45 Commando during the Falklands War. His book combines humour and humanity with a sharp eye for analysis. Gardiner won the 2018 Book of the Year with In the Service of the Sultan about his experiences in Oman with a similar combination. In both books he has a story to tell and he tells them very well. This year's shortlist also included David L Bradshaw's look at the Canadian contribution to Bomber Command, which combined insight and informed analysis with an excellent rebuttal of much of the ill-informed criticism of the bombing campaign; Two Sides of the Beach by Edmund Blandford an even handed and thought provoking account of the 1944 D Day Landings (which unusually had no single easily detectable mistakes) and finally Johnnie Johnson's classic Wing Leader about his time as a Second World War fighter pilot.

2021

OK..... drumroll..... magic envelope...... The winner of the 2021 Book of the Year is Agent Jack by Robert Hutton, a tale of Nazi agents, at least they thought they were, in Second World War Britain. Journalist Robert Hutton created a fascinating and very smooth read. The Jack of the title is former bank clerk Eric Roberts who posed as a British Nazi sympathiser and then the Gestapo’s man in the United Kingdom. It was fortunate that the people he recruited, some of them surprisingly good spies, were through Roberts reporting to MI5 rather than the Germans as they thought. Embarressment at how many of those born in the UK wanted to serve Hitler meant none were prosecuted and they went to their graves proud of their secret war against their fellow Britons. Hutton very narrowly beat another journalist, Douglas Liversidge with his account of the Second World War in the Arctic, another much neglected aspect of the conflict. Basically it came down to which topic was the most interesting and Hutton won by a hair’s breadth. Another runner-up was about one of the most written about clashes of the same conflict, the Battle of Britain. But official historian Denis Richards and former Hurricane pilot Richard Hough found much new to say. A combination of insight and knowledge meant they easily switched from Big Picture to anacdote in this even handed analysis of this myth muddied clash. The fourth book on the shortlist was RV Jones’s Most Secret War, quite rightly regarded as a classic memoir of the Second World War. Jones combined a sharp eye for amusing anecdote with insider knowledge of the battle between British and German scientists for technological advantage. Some of the battles between British scientists and bureaucrats were almost as bitter. I’ve just noticed the shortlist was all Second World War books, oh well.

2020

War in a Stringbag

by Charles Lamb

As I've written before, I think the main criteria for literary award judges should be "I wish I'd written that". Well, I couldn't have written the 2020 Book of the Year because I didn't fly a Royal Navy Swordfish bi-plane during the Second World War. But I do wish that I could tell a story as engaging as Charles Lamb does in War in a Stringbag. Lamb somehow mixes humility with humour, hilarity with horror, as he recounts his part in some of the most Royal Navy's most important actions in war. As well as an excellent raconteur, Lamb also shows himself to be a thoughtful and humane man. This is a book which easily justifies the claim that is a "classic". Lamb just pipped William Johnstone's A War of Patrols which takes a refreshingly honest look at the Canadian Army's part in the Korean War and puts the record straight when it comes to the much maligned battalions specially raised for the conflict. Iain Ballantyne's look at the activities of British submarines during the Cold War in Hunter Killers was the third book on the short list. An extraordinary and genuinely little known tale exceptionally well told.

2019

A rash of late contenders made it hard to choose the 2019 Book of the Year. The contenders included Commander by Stephen Taylor (Review 470); Lawrence of Arabia’s War by Neil Faulkner (Review 460); 1914-1918 by Lyn Macdonald (468); Marked for Death by James Hamilton-Paterson (450); Corps Commanders by Douglas Delaney (440) and The Lost Battle: Crete 1941 by Callum MacDonald (474). But at the end of the day it came down to Faulkener’s account of the First World War in the Middle East and Hamilton-Paterson’s account of war in the air 1914-18. Both were well written and took refreshing looks as subjects which many may have felt left very little new to say. Hamilton-Paterson came out top by the narrowest of margins for his insightful and informative approach which proved just slightly more thought-provoking than Faulkener. It was a very strong field and I would have little hesitation in recommending any of the contenders.

2018

In the Service of the Sultan

by Ian Gardiner

Well, the short list for the 2018 Book of the Year Award was very short - three books only. Dan Collins did a nice, not say sensitive job, of interviewing 25 winners of gallantry awards from Iraq and Afghanistan in his book In Foreign Fields. The former sports journalist obviously had a knack for getting soldiers to open up to him and tell their stories. The second runner-up also featured a gallantry medal winner. This time it was Australian SAS signaller Martin "Jock" Wallace in a story told by fellow Aussie journalist Sandra Lee. Lee succeeds in bringing Wallace to life and also the wintry Afghan mountainside where the SAS man and a company from the US 10th Mountain Division battled a determined and skillful Taliban force for 18 desperate hours in 2002. But the winner is In the Service of the Sultan by Ian Gardiner. The Sultan is the Sultan of Oman, a former Cameronians/Scottish Rifles officer, the time is the mid-1970s, and Gardiner is a young Royal Marine officer on attachment. He proves to be a born raconteur with a knack for putting his patter into very readable prose. He is also a skilled soldier, who would go to command a company of Royal Marines in the Falklands War, and the book is an excellent primer on small unit actions and counter-insurgency operations, in this case against communist-backed rebel tribesmen in the province of Dhofar. He also incorporates the experiences of many of his fellow officers serving the Sultan and has an obvious affection and respect for his Muslim soldiers. This book took an early lead in the search for the 2018 Book of the Year and never really lost it.

2017

The Manner of Men

by Stuart Tootal

The 2017 Book of the Year is....... drum roll....... The Manner of Men by Stuart Tootal. This year's shortlist was stronger than in many previous years and in a change of format there will be a list of the runners-up. Tootal took the title with this account of the 9th Parachute Battalion's attack on the Merville Battery on the morning of D Day in 1944 which prevented its guns being used to their full effect on the eastern wing of the Allied invasion fleet. Tootal, as a former parachute battalion commander in Afghanistan, showed an understanding of the problems faced by the 9th Battalion's leaders and how they were dealt with rarely seen in most recent books about the Second World War. And as a combat veteran he may have had more luck getting the surviving veterans of the 1944 battle to open up than many modern writers would. The accounts of the fighting are unflinching without tipping over into war pornography. He is also good on the internal power politics of an infantry battalion. OK, to the runners-up. Gallipoli by Peter Hart was a very strong contender. He more than captured the squalor and randomness of death on the Turkish peninsula in 1915. On a higher level he also made a strong case for the whole enterprise being doomed from the start and argues it would have failed even without the muddle-headedness and incompetence of the senior British officer corps. Zulu Rising by Ian Knight also only narrowly missed the top award. Knight busted many myths about the massacre of British troops at Islandwana in 1879 and the subsequent successful defence of the mission station at Rorke's Drift. He brought some much needed balance by paying more attention to Zulu accounts of the war.

2016

A Spy Among Friends

by Ben Macintyre

This year had a longer shortlist for the Book of the Year than has been seen for several years past. At the end of the day the winner was decided using the old "By Jings, I wish I'd written that" rule of thumb. And the book I wished I had written was A Spy Among Friends by Ben Macintyre. The spy being referred to in the title is the loathsome Kim Philby. The "friends" are the intelligence agents he took for a ride after he infiltrated British Secret Service on behalf of his Soviet masters in Moscow. Not included as "friends" are the numerous people murdered by the Communists acting on the information he supplied. Sadly, charm does not come through on the printed page - and Philby at his peak in the 1940s and 50s was said to be charming man. Personally, I found the Philby portrayed in this book, and several of his friends, loathsome. I suspect that was Macintyre's intent. Hindsight is always 20/20 but it is hard to believe that Philby would have lasted as long as he did if a number of people had done their jobs even competently. Macintyre does a great job of bringing the various characters and the world they inhabited to life. There have been many books written about Philby and his fellow upper class traitors, but few spell out so clearly the culpability of British Society in their crimes. It would be nice to think it could never happen again - but it could. A cautionary tale indeed. Anyway, Macintyre beat out Hew Strachan, for his wide-ranging and sober book of the TV series The First World War; Bob Shepherd for his memoir of his days as a private security consultant and bodyguard, The Circuit; and David Cordingly's excellent "biography" of a British warship during the Napoleonic Wars, Billy Ruffian. Robert Kershaw's look at the life and experiences of tank crews during the Second World War, Tank Men, would also have been in the running but for some silly factual errors.

2015

Gulf War One

By Hugh McManners

The 2015 Book of the Year has gone to a book that I almost put back on the shelf when I found it in a charity shop. Gulf War One by Falklands War veteran Hugh McManners looked, at first sight, like a bog-standard collection of literary sound bites about a conflict in 1991 which has pretty much slipped from popular memory. But McManners skillfully stitched the first person recollections into a coherent and highly readable account of Britons at war. Many of the interviewees were senior officers or politicians, including then Prime Minister John Major. McManners seems to have caught them in their more candid moments and the picture they paint is far from pretty, sometimes more reminiscent of the Crimean War than a modern conflict. Perhaps as so many were retired by the time the book was written that they were prepared to be more truthful than they could afford to be 20 years before. McManners also includes a strong sprinkling of squaddies. The picture that emerges is a credible mixture of bravery and jobs-worth-ism. There have been a lot of books written about the British Army's deployment to Afghanistan. I hope it will not be 20 years before someone produces a book of this one's calibre about that conflict.

2014

England's Last War Against France

by Colin Smith

In another context, journalism awards to be precise, I suggested that one of the main qualifications for the winner should be whether the judge can, or wants to, admit "Jeepers Creepers, I wish I'd written that". Well, I wish I'd been quicker off the mark and written about Britain's clashes with Vichy France during the Second World War. The French killed a lot of Britons and their allies but it's something that isn't discussed much. After the war, everyone was persuaded to pretend that the French were gallant allies. Everyone in France was, supposedly, in The Resistance. The truth is, of course, far more complex. Journalist Colin Smith does a good job of peeling away some of the rotten onion skin to get at something far closer to the truth. One of the reasons I know he did a good job is because I had already started compiling a file on the French and their collaboration with Nazi Germany. I'd already written, in Scottish Military Disasters, about No. 11 (Scottish) Commando's 1941 fight with the Vichy French on the Litani River in present-day Lebanon. And more recently I'd come across an account of the Royal Scots Fusiliers campaign in Madagascar. So, I knew there was a complex and intriguing story to be told. Smith's book only confirmed that. I doubt if I could have done a better job of telling this sorry tale than Smith did.

2013

The Bang-Bang Club

by Greg Marinovich and Joao Silva

The 2013 Book of the Year turned out to be a three-way race, and a very close contest at that. Eventually I decided to go with The Bang-Bang Club, a book about photographers I suspected before I started it that I wouldn’t like. I expected a self-indulgent tale of high-maintenance prima donnas and war junkies. Instead I found I was reading a thoughtful account of murder and mayhem in South Africa black townships in the run-up to the first democratic elections there in 1994. The other books in the running were The Taliban Don’t Wave by former Canadian Army officer Robert Semrau, who was court-martialed for executing a badly wounded Taliban fighter. It was one of the few Canadian books to come out of Afghanistan that did not paint Canadian troops as being, without exception, paragons of professionalism, courage and honesty. The Canadian military does attract some very high calibre people but it also has some flawed people. Writers who fail to acknowledge that are short-changing both the troops and the reader. However, making it Book of the Year would have meant three out of four awards going to books about Afghanistan. The third book in contention, Road of Bones by Fergal Keane about the 1944 Battle of Kohima against the Japanese. It was an excellent depiction of men at war from one of Britain’s top broadcast journalists but I couldn’t help feeling that it was beginning to run out of steam a few chapters before the end. That said, I’d highly recommend all three of these books and any one of them could have won the 2013 Book of the Year.

2012

Dead Men Risen

by Toby Harnden

I don’t know if this doorstep of a book (656 pages) is indeed “the defining story of Britain’s war in Afghanistan” as claimed on the front cover. But I can say it is one of the best I’ve read. Daily Telegraph journalist Harnden, a former Royal Navy officer, takes a detailed and hard look at the Welsh Guards’ operations in Afghanistan in 2009. The story is seen mainly through the eyes of the officers and senior non-commissioned officers, but is none the worse for that. It is a tale of stoicism and flashes of bravery. Grown men cry. But it’s also a balanced account and several men in the book lose their bottle. There are also accusations of incompetence and cowardice. The Labour Government of time comes in for harsh criticism for under-resourcing its troops in Afghanistan. Senior commanders are also criticised for ill-judged strategies and tactics. Although Harnden doesn’t name names, some senior officers seemed to have been telling Labour that they could do the job with the resources available and then briefing the Tory opposition at the time about shortages of crucial equipment. There’s little doubt that Harnden does not approve of the British policy of spreading their troops too thinly across Helmand and ending up controlling no territory beyond the range of their rifles. Nearly every foot patrol ends up fighting its way back to base. Roadside bombs take a heavy toll of the soldiers. The senior commanders initially putting the success of the bombs down to the incompetence of the soldiers sweeping for them, rather than the sophistication of the bomb makers, is a very telling indictment of the men running the campaign. The message of this book is clear – if you’re going to fight a war, do it properly. But this book is not a polemic, it is a snapshot of the Brits at war and a good one. Harnden gives voice to the men on the ground who question not only how the campaign was being fought in 2009 but whether it should have been fought at all.

2011

The Sharp End

by Tim Cook

If I was offering a prize for the best military history book I've read in the past year, this would be it. The book is the story of the Canadian Army during the first two years of the First World War. But I'd recommend it to anyone interested in the First World War, or any war for that matter.

Cook, the Canadian War Museum's expert on the conflict, has delved deeply into both the official records and private letters, to tell the story of the Canadians as they built up their army from a few regulars and Boer War veterans into one of the crack formations on the Western Front. Mistakes were made, many mistakes, and Cook doesn't shy away from discussing them. Nor to does he avoid some of the unpleasant truths, such as the execution of prisoners. His unblinking eye roams freely over the bickering and petty jealousies of the senior officers and the misery of the frontline soldiers' lives in the trenches. Few who sailed with the First Contingent made it back to Canada unscathed and many did not come back at all. Battalions are wiped out in desperate battles which achieved little. Cook cleverly weaves discussion of various aspects of the soldiers' lives, from medical care to leave arrangement and food, in between accounts of these battles.

He has a great eye for a telling quote drawn from a letter home or a diary which brings the horror of the first industrial war to life. Those of you who've read Scottish Military Disasters may remember that I was dismissive of the true combat value of the bayonet, beyond scaring the living daylights out of an already shaken foe. But Cook's changed my mind. He's right when he argues that few men were treated for bayonet wounds because bayonet fights were usually to the death. If there was ever a conflict where the bayonet might have had some value it was in the rat-trap trenches where there was nowhere to run and a bullet could just as easily kill a friend as a foe. The invention of the submachine-gun had changed things by the time the Second World War came around.

I'm starting to judge books about the First World War by the way they treat Haig and his senior commanders. Cook is fair and realistic. I suspect one reason why Cook's work stands head and shoulders above much writing on Canadian military history is that he has a wide knowledge about the First World War as a whole. Too many other writers' claims of amazing Canadian innovation are based on a profound ignorance of what was going on in the British Expeditionary Force outwith the Canadian Corps.

2010

An Ordinary Soldier and Task Force Helmand

By Doug Beattie, with Philip Gomm

Looking in the bookshop at Heathrow Airport recently I got the impression that every soldier who has served in Afghanistan has written a book about their time there. If you can only read one, or maybe two, then this read something by Doug Beattie.

As a mentor and trainer to first the Afghan National Police, in the first book, and the Afghan National Army, in the second, Beattie went toe-to-toe with the Taliban nearly every day he was in the field. This stuff is from the heart and not second-hand, as told to a journalist or some flabby ex-soldier turned writer. Beattie insists that he's just an ordinary soldier and is full of praise for the small team of British squaddies, often not obvious hero material, who took the war to the Taliban. He doesn't pull many punches with his opinions and is often outspoken. It was only towards the end of An Ordinary Soldier that I realised that the first draft had been written as a form of self-therapy following his return home from his first deployment to Afghanistan.

This book comes from an unusual viewpoint because Beattie rose through the ranks to Regimental Sergeant Major and then became one of the few late-entry officers not to be shunted off behind a desk as battalion family welfare officer but to actually see frontline action. Beattie is a character, a real scrapper, and brings perspective sadly too seldom seen in military books. He certainly didn't trigger my bullshit detector.

Online

We have 316 guests and no members online